| [94]

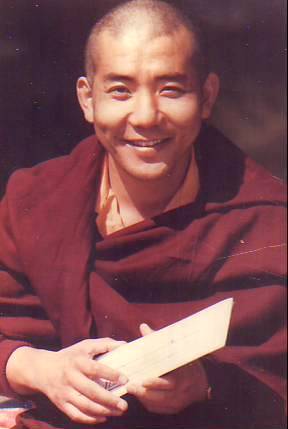

His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche the Third,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge

Instructions on “The Supplication:

Calling the Lama from Afar”

composed by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye

The Motivation

It’s important to have a pure motivation when receiving Dharma instructions. Pure motivation means receiving and listening to the teachings with Bodhicitta (‘the mind of awakening’). What does this mean? When you receive Dharma teachings, you think, “I am receiving an explanation of the Dharma in order to be able to establish all sentient beings in the state of perfect Buddhahood.” Please receive the teachings with this attitude.

It’s said that a listener can have three faults while receiving Dharma teachings, which need to be avoided. They are explained by metaphor. The first is forgetfulness, which means not holding what is said in the mind. It’s like a broken cup that has a hole in the bottom - whatever is poured into the cup automatically leaks out again. The second fault is being distracted. It’s compared to a cup turned upside down - nothing can be poured into the cup. The third fault is receiving the teachings while having afflicting thoughts. It’s like a cup with poison in it - whatever liquid is poured into the cup immediately turns into poison. Therefore, please receive the teachings free of the three faults and with a pure motivation.

The Lineage Prayer

“Namo Guru.”

The supplication, “Calling to the Lama From Afar,” is well-known to everyone. The key to invoking blessings is devotion, which is aroused by sadness and renunciation. This is not a mere platitude but is born in the center of one’s heart and in the depths of one’s bones. With decisive conviction that there is no other Buddha greater than the Guru, one recites the melodic verses of the supplication.

During this seminar, I am not going to explain the Three Roots or the Gurus of the Lineages. There isn’t anything difficult to understand that needs to be explained. But if there is anything that you don’t understand, please ask during the question and answer session. One or two names in the first section might be unclear, though. One of the Lamas mentioned is Omniscient Drime Özer; he is more commonly known as Longchenpa or Kungchen Longchen Rabjampa. Another name you might not know is Omniscient Dolpo Sangyä, Kunchen Dolpopa; he is the founder of the Jonang Tradition and is a Lineage-holder of the Shentong School of Madhyamika. Towards the end of the first part of “The Supplication,” Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo is referred to as Ösel Tulpay Dorje and Jamgon Lodrö Thaye is referred to as Yongten Gyamtso.

The Instructions

The Four Contemplations that Help Turn the Mind Towards the Dharma

1) Samsara

The second part of the liturgy is the main part of the instructions. The first Tibetan words in the second part are “kye-ma”; these words are an expression of sadness. The text in English is:

“Alas, sentient beings like ourselves, who have committed negative actions,

Wander in samsara from beginningless time.

Still experiencing endless suffering,

We do not feel even an instant of repentance.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that renunciation arises from the depth of our heart.”

In order to practice the Dharma, the first thing that is necessary is to understand that samsara has no value. If you don’t realize this, then you’ll hardly see a reason to practice. On the other hand, if you do see that samsara has no value, then you are inspired to turn your mind towards the pure Dharma. This is why in “The Dorje Chang Lineage Prayer” it says, “Revulsion is the foot of meditation practice.”

Generating the pure motivation to turn towards the Dharma has to be based on renunciation. Some people think that renunciation means trying to flee or run away from samsara, which isn’t what renunciation means. It means actually seeing that samsara has no value. You can’t simply run away from samsara. It’s necessary to see that it’s like a water wheel, where one kind of suffering leads to the next kind. Although we don’t want to suffer, we do because we think that samsara has a reliable basis. While doing what we can to be happy, we intensify our mental afflictions and this leads to an accumulation of more karma and suffering. Therefore, at the beginning of the second section of “The Supplication,” we first pray to give rise to renunciation. This is also the reason in the preliminary practices or Ngöndro, the first thing to be practiced is what is called “the four thoughts that help turn the mind.” The four thoughts lead us to turning our mind away from the misconception that samsara has value and turning the mind towards the understanding that it doesn’t have a reliable essence. This doesn’t imply fleeing samsara, rather, it means seeing that samsara has no essence. If this kind of turning of the mind or renunciation of samsara is not accomplished, then any Dharma practice we do becomes what is called “spiritual materialism.” In that case, instead of being a remedy for the confusion and suffering experienced in samsara, we generate further confusion and suffering.

The conventional and relative appearances that we apperceive and experience aren’t real. To attain liberation, the way we apperceive things needs to be changed and end. People think that ending confusion puts an end to ordinary appearances and then one experiences rainbows, lights, and so forth. But this is not the case. As Tilopa told Naropa, “It is not by appearances that you are fettered, but by your fixation on them.” This means that what appears to us isn’t a problem, rather, the way we apprehend things and fixate on them is wrong and needs to be remedied.

Phenomena do not need to change, rather, we need to change the way we perceive and apperceive things. For example, the table in the room doesn’t need to be changed nor is there anything to the table that forces us to fixate upon it. The Buddha never taught that it’s necessary to destroy, alter, or block appearances and experiences that arise or to make them cease. In fact, it’s taught that although conventional and ultimate realities seem contradictory, the correct view of the basis of reality is the inseparability of the two truths. Taking the table, its appearance is the basis for imputing that it exists. While it appears, it is empty of being what we assume and label it to be. Actually, the table lacks inherent existence and is a collection of particles that are interdependent. The fact that the table consists of many parts and is thus a conventional reality but lacks inherent existence doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

How, then, does a Buddha experience phenomena? A Buddha apperceives phenomena as the inseparability of appearances and emptiness and sees phenomena like a magical illusion. We, on the other hand, apprehend phenomena as solid, inherent existents. As a result, we divide our experiences into an apprehending subject and apprehended objects. A Buddha doesn’t do this. In fact, if things weren’t empty of inherent existence, they couldn’t arise and appear.

What does this have to do with renunciation? Let’s take something we own and are very possessive about. If we lose it or if it breaks, our feeling doesn’t diminish or end because we fixate upon another object that we are possessive about. This shows that it’s the mind that is fixated on objects and that objects don’t need to be changed. Therefore the Buddha taught that “All things are the expression of the mind.” Understanding this moves us to give rise to renunciation from the depth of our heart.

2) The Precious Human Birth

The second verse of “The Supplication” deals with the difficulty and benefit of obtaining what is referred to as “a precious human birth.” The verse is:

“Although we have attained a precious human birth with leisure and resources, we waste it in vain,

Constantly distracted by the activities of this hollow life.

When it comes to accomplishing the great goal of liberation, we are overcome by laziness

And return empty-handed from a land filled with jewels.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we make this life meaningful.”

A human existence is superior to all types of existences in the six realms of samsara. There are two types of birth with a human body. They are: a plain human existence and a precious human existence. A precious human existence means having attained the eight freedoms and ten resources to achieve Buddhahood. By having accumulated a great amount of merit in previous lifetimes, we all have a precious human existence. However, we might be wasting this special opportunity by striving to accomplish temporary aims and thus by not engaging in activities to attain Buddhahood. In fact, everything we do to gain short-term goals causes us to suffer and in some cases even causes us to lose our lives.

Engaging in senseless and meaningless activities is what defines samsara. Engaging in meaningful activities is what practicing Dharma means. The purpose of practicing the Dharma is to establish ourselves in complete and perfect Buddhahood and thus being truly able to help all living beings attain the same result. Although we know this, we are distracted and put off practicing to another time. This is like reaching a treasure island and returning home empty-handed. We haven’t only attained a precious human body, but we have actually met spiritual teachers and received Dharma teachings on how to practice from them. Therefore it’s stated in the above verse: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we make this life meaningful.” We recite this prayer so that we are inspired to make use of our lives, i.e., to free ourself and all sentient beings from samsara.

3) Death and Impermanence

The next verse of “The Supplication” is about death and impermanence. The verse about death is:

“There is no one on this earth who will not die.

Even now, people are passing away, one after the other.

We also soon must die,

But like a fool, we plan to live long.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we curtail all of our scheming .”

Everything that we experience – life in its entirety, too - is impermanent and of indefinite duration. Lord Buddha displayed the transitory nature of all things when he passed into Parinirvana and left his body behind.

Every phenomenon that is compounded eventually falls apart or dies. If we look around, we see that, one after the other, people and animals die. We need to realize that we, too, will die, but we don’t know when. When somebody who is close to us dies, we think, “Oh, I will also die, so I had better make preparations.” But we forget, return to what is called “having a long attitude,” and live our lives as usual. It’s a fact that there’s no guarantee that we will be alive the next day, and nobody can rightly say, “I will be alive in a few days or weeks.” Nobody can even know if they will be alive in the next minute or second. That’s why it’s stated in this verse: “But like a fool, we plan to live long.”

The last lines of this verse are a supplication: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we curtail all our scheming.” This means to say that we aspire to give up the tendency to think that we will live forever. The first lines of this verse are recited so that we realize that we might die at any time and that there’s no time to waste. This verse teaches us about the importance of contemplating death so that we practice the Dharma.

The next verse deals with impermanence. It is:

“We will be separated from our closest friends.

Others will enjoy the wealth we as misers kept.

Even our body we hold so dear will be left behind.

And our consciousness will wander without direction in the bardos of samsara.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we realize the futility of this life.”

When we die, we are alone; no family member or friend can help us. We planned to use the things that we collected at a later time in life and as a result failed to offer them to the Three Jewels or didn’t share them with people in need. After we have died, our consciousness wanders aimlessly in the Bardo, without a destination and without any freedom to be generous. Even if we don’t attain Buddhahood in this life, in the Bardo after death, our practice will help us be fearless and not to experience suffering due to being separated from our friends and possessions. Therefore the verse is: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we realize the futility of this life.”

Everything that we have is of no use to us whatsoever after we have died. Our friends and family members won’t be able to help us, our body will be a corpse, our savings won’t buy us free, because Yama, the Lord of Death, cannot be bribed. Therefore we supplicate that we stop being attached to people and things during life so that we have no attachment when we die. This is how practicing Dharma during life benefits us when we die.

4) Karma

“In front, the black darkness of fear waits to take us in;

From behind, we are chased by the fierce red wind of karma.

The hideous messengers of the lord of death beat and stab us,

And so we must experience the unbearable sufferings of the lower realms.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we are liberated from the chasms of lower realms.”

Having contemplated death and having practiced the Dharma well during life, then dying and death aren’t problematic for us. In fact, a practitioner can be liberated in the Bardo between death and rebirth. Whether we practice Mahamudra by looking at our mind, visualize a Yidam deity, and so forth, attachment merely weakens through any practice that we do while alive. However, the moment we die, the appearances of things that we are attached to cease for a while and the true nature of our mind, which is called “the clear light of death,” appears to us clearly and directly. We can attain liberation if we recognize it. If we don’t, we continue our journey through the Bardo of Dharmata (‘the Bardo of the true nature of things’). Then mind’s unimpeded awareness arises in the form of the 100 peaceful and forceful deities. If we realize that they are an expression of our mind’s own nature, we attain liberation.

The five aggregates that we apperceive during life appear as the five pure male Buddhas after we have died, and the five elements that we experience during life appear as the five pure female Buddhas after death. The eight consciousnesses are then experienced as the eight Bodhisattvas, and so forth. When we meditate these deities during life, it’s an imaginary practice, but after death they appear to us directly. If we fail to recognize them after we have died, then we feel wrapped up or entangled in what is metaphorically called “the black darkness.” This doesn’t connote floating around in space, rather, lacking control, we are driven and hurled around by the karma that we accumulated in all lifetimes. If we fail to recognize the peaceful and forceful deities as the display of our own mind, then we see them as threatening apparitions that we fear will torture and kill us. We suffer very much and flee, thus creating emotional states that are a proximate for rebirth in a lower realm of existence. That is why we pray: “Lama, think of use, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we are liberated from the chasms of lower realms.”

Obstacles to Practice: The Eight Worldly Dharmas

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye offered general instructions that need to be acknowledged in this section of the supplication, “Calling the Lama From Afar.” The first verse concerns pride:

1) Pride

“ We conceal within ourselves a mountain of faults;

Yet, we put down others and broadcast their shortcomings, though they be minute as a sesame seed.

Though we have not the slightest good qualities, we boast saying how great we are.

We have the label of Dharma practitioners, but practice only non-Dharma.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we loose our pride and self-centeredness .”

Everybody has faults. Because we don’t like being criticized, we tend to hide our faults. If somebody points them out in a slight way, we become angry, and if somebody points them out in an even slighter way, we become even angrier. On the other hand, we think it’s our duty to point out others’ faults and to even criticize them in public. Although we don’t have exceptional qualities and there’s no reason to think that we’re better than other people, we think we are superior and are very proud of ourselves. Furthermore, we don’t practice, yet we call ourselves Dharma practitioners. It’s very cunning to try to deceive others by calling oneself a practitioner, and only few things are worse. Therefore it’s written in the above verse: “Bless us that we loose our pride and self-centeredness.”

2) Ego-fixation

“We conceal within the demon of ego-clinging that always brings us to ruin.

All of our thoughts cause kleshas to increase.

All of our actions have non-virtuous results.

We have not even turned towards the path of liberation.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that grasping onto a self be uprooted.”

The purpose of this verse is to cut through “bdag-‘dzin,” the Tibetan term for ‘self-fixation.’ In Buddhism, it’s taught that there are two kinds of imputed self-identities. One is “gang-zag-gi-bdag” (‘the self of persons’) and the other one is “chös-kyi-bdag” (‘the postulated self of phenomena’). Gang-zag-gi-bdag is based on taking what is not a self to be the self of a person.

Traditionally, it’s taught that we postulate a self on the bases of all or some of our five aggregates. As a result, we call phenomena that we perceive “mine,” e.g., “my table, my room, my world,” and so forth. In other words, we divide things that we perceive and experience into an apprehending subject (ourselves) and apprehended objects (others). After having perceived an appearance and after having felt an experience, we create a dualistic split by postulating a truly existing self in opposition to truly existing objects. Then the three root afflictions arise. These root afflictions are ignorance as to the way things truly are, attachment to that which is identified as the self, and fear of or aversion towards that which is experienced as other than the self. The innumerable hostile, mental afflictions (such as pride, jealousy, and so forth) are born from these three root afflictions, i.e., mind poisons. The three main mind poisons determine our actions that leave an imprint in our ground consciousness. These imprints are stored there as habits and tendencies. Created by our actions, these imprints or habits are the reason we experience samsara the way we do - they are like the cups in the wheel of a watermill. Karma is the ripening of past actions into experiences. Since the root of negative karma and the ensuing experiences of samsara are due to the imputation of an inherently existing self, which is referred to as “the demon of ego-clinging” in the above verse, the erroneous imputation must be cut in order to turn “towards the path of liberation.” Therefore we recite and contemplate the last line that “grasping onto a self be uprooted.”

When hearing about fixation on a self, many people think that this refers to something that is self-existent. In fact, nothing is inherently self-existent. Fixation is based on the habit of misconceiving and believing in a truly existing self. Since no self exists the way we think and believe, there’s nothing that needs to be abandoned. If there were a truly existing self, it wouldn’t be hard to find and simply remove while on the path of liberation. Practice consists of eradicating our fixation, and the only way to do this is by cultivating mindfulness, attentiveness, carefulness, circumspection, compassion, and so forth, in all activities and at all times. Other than these practices, there are no other means to abandon the habit of fixating on the misconception that a self truly exists.

Having engaged in rigorous theoretical studies, many students accept the view that the self doesn’t exist the way it is conceived. But believing in the non-existence of a self isn’t the same as actually realizing freedom from ego-fixation. Freedom from ego-fixation can only be won through practice. It’s gained by overcoming the habit of viewing the self as a truly existing entity and not by attempting to eradicate the wrong belief in it.

3) Impatience

“A little praise makes us happy; a little blame makes us sad.

With a few harsh words, we loose the armor of our patience.

Even if we see those who are destitute, no compassion arises.

When there is an opportunity to be generous, we are tied in knots by greed.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that our mind be one with the Dharma.”

In this verse of “The Supplication,” Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye tells us that words and ideas aren’t helpful when practicing the Dharma, rather, that it’s important to integrate Dharma practice in our ground consciousness, i.e., our mind needs to become mixed and mingled with the noble principles of the Buddhadharma. For example, it’s taught that samsara and nirvana are inseparable and that we should rest in equanimity, but usually our actions contradict these teachings. As stated in the first line of this verse, we are delighted when someone speaks kindly but displeased when somebody speaks badly about us. Either way, the words aren’t relevant, rather, our reactions to those words. In some cases, it might be necessary to appreciate and acknowledge what somebody honestly means when he criticizes us. So, although it’s repeatedly taught that we need to meditate and practice patience, we don’t even tolerate slightest criticism.

The third line in the above verse deals with whether we have real compassion or not. Although we have been taught to have compassion for all living beings, especially for those who are suffering, we don’t react with compassion when we see people or animals in desperation. Often we look down on them with a pitiful glance and think, “It’s their karma! It’s their problem, not mine!” We might think, “I don’t have any change right now,” or “If I give him money today, I’ll have to give him money every day.” Therefore the next line in the above verse reminds us that usually we have many excuses for not being generous towards somebody we see who is in need. In fact, when we encounter poverty-stricken people or abused animals, we often hope that they won’t touch us. All this shows that our practice is only comprised of words, in which case we might believe in the Dharma but aren’t practicing it. Therefore the last line is: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that our mind be one with the Dharma.”

4) Attachment

This fourth verse of the section on the obstacles to practice points to being discontent, which is the major reason we suffer. The verse is:

“We think samsara is worthwhile, when it is not.

We give up our higher vision for the sake of food and clothes.

Although we have all that is needed, we constantly want more.

Our minds are deceived by unreal, illusory phenomena.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we let go of attachment to this life.”

The first lines tell us that samsara is meaningless and that we mistakenly think that the things we experience are real and worth all the trouble to obtain and own. Of course we need a shelter, food, and clothing, but they aren’t everything in life. When we have enough, it’s important to be content and not to forfeit our pure intention to practice the Dharma for the sake of attaining more than we actually need. It’s usually the case that people who have 100 things want 1000, and when they have 1000 things, they want 10,000 - they are rarely satisfied with having more than enough. This lack of contentment is the main cause of suffering.

Jetsün Milarepa taught that many very wealthy people who have more riches than they need and more than they could possibly ever use are quite miserable. In the beginning, they went through the agony of acquiring things. When they succeeded in having what they wanted, they go through the agony of holding on to their possessions and fear losing what they hold on to so tightly. Jetsün Milarepa had no possessions but was quite happy and content. Therefore the above verse closes with the supplication: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we let go of attachment to this life.”

5) Non-Virtuous Activities

“Not able to endure the merest physical or mental pain,

With blind courage, we do not hesitate to fall into lower realms.

Although we see directly the unfailing law of cause and effect,

We do not act virtuously, but increase our non-virtuous activity.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we come to trust completely in the laws of karma.”

Every living being wants to be happy, and nobody wants to suffer. Since suffering isn’t a cause but is a result, avoiding detrimental situations won’t eliminate suffering. To eliminate suffering, we need to avoid the causes of suffering. And the causes of suffering are karma and the ensuing mental afflictions that are stored in the ground consciousness as habitual tendencies and that are repeated when causes and conditions prevail. It’s for this reason that the Buddha taught the First Noble Truth, which is: The truth of suffering is that which is to be known. He taught the Second Noble Truth, which is: The truth of the cause of suffering is that which is to be avoided. This means to say that suffering will not end as long as we haven’t abandoned our mental afflictions and given up non-virtuous activities.

The above verse points out that although we cannot bear any suffering and have learned that non-virtuous actions lead to lower realms which entail much anguish and pain, we are fool-hardy enough to resist engaging in virtuous activities. We can determine by means of direct valid cognition that the results of non-virtuous actions are suffering, but we ignore the logical evidence and continue engaging in non-virtuous activities. Therefore we recite the aspiration of this verse, namely, “that we come to trust completely in the laws of karma.”

6) Laziness

“We hate our enemies and cling to friends.

Lost in the darkness of ignorance, we do not know what to accept or reject.

When practicing Dharma, we fall into dullness, drowsiness, and sleep.

When not practicing Dharma, we are clever and our senses are clear.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we overcome our enemy, the kleshas.”

It’s necessary to rely on the remedies in order to reliably overcome the various mental afflictions. As it is, we feel aversion towards things that displease or frighten us, and we are attached to things that make us happy. Thus we are ignorant about what should be accepted and what should be rejected. Furthermore, although our intention is virtuous, we might become sluggish, for example, by falling asleep while meditating or by being inattentive while receiving Dharma instructions. On the other hand, we are very attentive when our intention is dominated by the mental afflictions and while engaging in non-virtuous activities. Therefore the supplication to our Lama in the above verse is: “Bless us that we overcome our enemy, the kleshas.”

7) Anger

“From the outside, we appear to be genuine Dharma practitioners;

On the inside, our minds have not blended with the Dharma.

We conceal our kleshas inside like a poisonous snake.

Yet when difficult situations arise, the hidden faults of a poor practitioner come to light.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we ourselves are able to tame our mind.”

In the first two lines of this verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye pointed to the fact that someone might appear to be a good Dharma practitioner while actually they have not mixed their mind with the Dharma. In the third line he compared them to a poisonous snake. Now, snakes are quite colourful, but the more colourful they are, the more poisonous they are. This metaphor applies to us, too. On the outside we can appear to be colourful and active practitioners, while, in truth, we conceal the poisonous snake that lurks within and suddenly strikes out when adverse situations arise.

The supplication to our Lama in the last line that we recite tells us what we need to do in order to be Dharma practitioners, namely, we need to tame our mind. The line is: “Bless us that we ourselves are able to tame our mind.”

8) Mental Instability

“Not recognizing our own faults,

We take the form of a Dharma practitioner, while engaging in non-dharmic pursuits.

We are habituated to kleshas and non-virtuous activity.

Again and again virtuous intentions arise; again and again they are cut off.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we see our own faults.”

This verse, which is similar to the foregoing one, deals with the eighth worldly dharma. Here, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye emphasised the importance of continuously practicing by always being attentive and thus recognizing what is taking place within our own mind. The first two lines describe the result of failing to recognize our faults.

On the outside, it might look like we are Dharma practitioners, while in truth we act under the power of our habitual mental afflictions. We repeatedly generate the good intention to practice the Dharma well, but by failing to be mindful and aware, our good intention wears off real fast and we forget it. That is why we recite the supplication to our Lama to bless us so that we clearly see what is taking place in our mind and to recognize our own faults. The supplication to our Lama is: “Bless us that we see our own faults.”

In this section of the sacred spiritual song, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye dealt with the eight obstacles that arise while practicing the path to mental refinement. These obstacles are called “the eight worldly dharmas.” So that we maintain and never lose the pure motivation of benevolence and compassion, he offered prayers of supplication to his Lama at the end of each verse. We are free to recite these lines with devotion for our Lama.

The Antidotes for the Eight Worldly Dharmas

I want to remind everyone that when we study or receive teachings, we need to have the pure motivation. Bodhicitta is the key that we hold in our hands to further and further develop a living appreciation of the Buddhadharma.

1) Renunciation

“With the passing of each day, we come closer and closer to death.

As each day arrives, our mind gets more and more rigid.

Though we serve the Lama, our devotion is gradually obscured.

Our love, affection, and pure outlook towards our Dharma friends diminish.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we tame our obstinate mind.”

In the first verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye described the importance of Dharma practice, especially for Vajrayana practitioners, and in which way practice can diminish instead of increase. He began by warning us about being rigid and reminds us of the importance of practicing.

Rigidity impedes us from practicing, and the closer we are to death, the more we need to be prepared by taming our mind. Devotion for our Root Guru, gaining the sacred outlook, and loving kindness and compassion should increase in our mind as we approach death. But after having been greatly inspired by our Guru, our devotion becomes weaker and weaker with the passing of time. In the same way, our respect for those with whom we have received Vajrayana empowerments (our Vajra brothers and sisters) diminishes. It’s extremely important to always respect, uphold the sacred outlook towards them, and never to break the sacred connection we have with them. Since we haven’t subdued our mind, there’s the danger of becoming weary and of breaking the bond we have with our Vajra family. Therefore we pray: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that we tame our obstinate mind.”

2) Refuge

“Although we have taken refuge, engendered bodhichitta, and made prayers,

Devotion and compassion have not arisen in the depth of our being.

Dharma activity and the practice of virtue have turned into hollow words;

Our empty achievements are many, but none have moved our mind.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that whatever we do is in harmony with the Dharma.”

Taking refuge, arousing Bodhicitta, having faith and devotion in the objects of Refuge, and having compassion for sentient beings are the roots of any Dharma practice. If we don’t have them, these practices are just words. They need to become part and parcel of our mental continuum by generating what is said to be “upwards faith and downwards compassion,” i.e., faith in the Three Jewels and compassion for all sentient beings. Simply reciting “The Supplication” without having faith and compassion will not suffice to actually tame our mind. In “The Lotus Sutra” it is stated: “Somebody without faith is like a burnt seed that, if planted, can never grow into a sprout. Likewise, somebody without faith can never give rise to qualities of being.” This means to say that it’s impossible to proceed on the path to liberation as long as we don’t give rise to Bodhicitta. Therefore we supplicate: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that whatever we do is in harmony with the Dharma.”

3) Bodhicitta

“All suffering arises from wanting happiness for ourselves;

Although it is taught that enlightenment is attained through benefiting others.

We engender bodhichitta, while secretly cherishing our own desires.

We do not benefit others, and further, we even unconsciously harm them.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we are able to exchange self for other.”

Everybody wants to be happy, but the create suffering by wishing for their own happiness and as a result, by ignoring others for the sake of selfish ambitions. It’s recorded in Sutras and Tantras that the Buddha taught that the principal cause of Buddhahood is altruism, the genuine wish to benefit others. In this verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye tells us about the importance of developing the wish to work for the welfare of others.

Instead of wishing for our own happiness and instead of not caring whether others suffer, we give rise to the altruistic attitude by genuinely wishing that all the happiness and causes of happiness we enjoy be experienced by all sentient beings and that we take on all the suffering and causes of suffering that living beings endure. This is what is called “exchanging self for others.” It is taught a great deal in the mind training instructions. In short, rather than having superficial wishes and ideas, it’s crucial to generate pure and genuine Bodhicitta.

4) Devotion

“Our Lama is actually the appearance of the Buddha himself, but we take him to be an ordinary human being.

We come to forget the Lama’s kindness in giving us profound instructions.

We are upset if we do not get what we want.

We see the Lama’s activity and behavior through the veil of doubts and wrong views.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that, free of obscurations, our devotion increases.”

This verse speaks about the importance of relying on a genuine Lama and on having unwavering devotion in him.

In general, we can rely on various kinds of teachers, depending on the knowledge or level of practice we are pursuing. Some teachers are quite intelligent and provide us with lots of information; they are respected as ordinary teachers. Within the context of Vajrayana, the spiritual teacher is much more important than an ordinary teacher and is seen as a Buddha. Our Root Guru introduces and transmits to us the ultimate nature of our mind and through his blessings, he can cause us to attain ultimate realization of the true nature of all things, i.e., the wisdom of all Buddhas. Since he has this ability, he is the embodiment of all Buddhas of the three times. We often make the mistake and don’t see our Lama in this way, as the first line states, “we take him to be an ordinary human being.”

As long as we haven’t received Dharma teachings or practice instructions, we are eager to receive them from a qualified Lama. When we have what we wanted, we forget who gave them to us. Some people even say, “I taught myself. I didn’t need anybody.” This is what is meant in the above line: “We come to forget the Lama’s kindness in giving us profound instructions.” It can also happen that we are disturbed or become resentful if our Lama doesn’t give us what we asked for, which isn’t the way to be. It can happen that we are very happy when our Lama praises us for anything we do and in response we fold our hands to our heart and say, “I go for refuge in my Lama,” but when he criticizes us, we turn away from him. This is wrong. It’s important to understand that our attitude and devotion need to be uncompromising.

The next point addressed in the above verse is to not “(…) see the Lama’s activity and behaviour through the veil of doubts and wrong views.” This means to say that once we are connected to our Lama, we need to have unfaltering conviction that his words and actions are beneficial and true. In the life stories of great Kagyü masters, we read that if the Lama told his disciple that fire is water or water is fire, the disciple believed him. By having the very same trust and devotion in our Lama, we are able to receive the blessings of the Lineage that he bestows and thus will be able to experience realization of the true nature of our mind. But having devotion doesn’t mean giving in to blind faith.

Before becoming committed to a Lama, it’s important to examine and choose him very carefully. Being committed and bound to a Lama isn’t the same as receiving instructions from a spiritual teacher. So that the connection is fruitful, we need to develop the sacred outlook and as a result we will be able to relate to our Lama as a living Buddha. Therefore the supplication of this verse is: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that, free of obscurations, our devotion increases.”

5) Confidence

The verse that deals with confidence is one of the most important verses in “The Supplication.” In the lines of this verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye explained the ultimate and true nature of our mind. He wrote:

“Our own mind is the Buddha, but we do not recognize it.

All concepts are the dharmakaya, but we do not realize it.

This is the uncontrived natural state, but we cannot sustain it.

This is the true nature of the mind, settled into itself, but we are unable to believe it.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that self-awareness be liberated into its ground.”

The first point to be understood is that liberation from samsara or Buddhahood cannot be sought in a place that is located outside or is other than our own mind. The only difference between a Buddha and an ordinary living being is whether we have realized our mind’s true nature or not. Our mind’s essence has never been diluted or corrupted by mental afflictions or illusions, so it doesn’t need to be liberated. It always was, is, and will be a Buddha. Yet, we are bewildered and confused because we have not recognized our mind’s limitless, open essence and thus mistakenly take our mind’s emptiness to be a self. Furthermore, by not recognizing the manifestation of our mind’s lucidity, we mistakenly take appearances to be other than our mind. And so, by failing to recognize our mind’s emptiness, we fall into the extreme of nihilism, i.e., negation; and by failing to recognize our mind’s clarity, we fall into the extreme of eternalism, i.e., the belief in a permanent self of inner and outer phenomena. The true nature of everyone’s mind is the inseparability of emptiness and clarity. Therefore Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye wrote: “Our own mind is the Buddha, but we do not recognize it.”

As it is, we continuously have many thoughts and, regardless of what we think about, every thought is a manifestation of our mind and not other than it. Our mind, which is not different than that of a Buddha, is a Buddha’s three bodies. This means that our mind’s essence is the Dharmakaya, its nature is lucid clarity (the Sambhogakaya), and its aspects are the manifested display of thoughts (the Nirmanakaya). This is expressed in the first line of the above verse: “All concepts are the dharmakaya, but we do not realize it,” i.e., since our thoughts are the display of our mind, they are our mind’s true nature, which is emptiness, the Dharmakaya.

It’s important to understand that thoughts are not empty after they have ceased, rather, they are empty at the time that they appear. Following after a thought is conceptualizing another thought, one after the other. If we don’t follow after a thought that we have and make further thoughts, then it’s liberated the very moment that it arises. When a thought is simultaneously liberated the moment that it arises, the energy of the mind is no longer referred to as “a thought” but as “wisdom.” Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche therefore wrote in the next line: “This is the uncontrived natural state, but we cannot sustain it.” That is, since our mind’s true nature has never been diluted or corrupted by mental afflictions and illusions, from time to time everybody experiences what is called “the uncontrived, unfabricated mind.” Since we don’t recognize it, we can’t sustain or maintain it.

“Uncontrived” can be explained as following: After having received Mahamudra instructions from our Lama, we examine to see what our mind is like and then rest evenly in our discovery. Resting evenly in non-fabrication refers to the time that we have stopped examining and thinking about our mind. The uncontrived mind that we usually don’t recognize is always present. While practicing, we rest in our mind’s natural presence, without attempting to restrict the meaning of Mahamudra by defining or describing it. As taught by the Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, in “The Aspiration Prayer of Mahamudra” that he composed: “Being free from mind productions, it is the Mahamudra.” And so, for the person who rests in the experience of the uncontrived, unfabricated mind, there is no meditator, no meditation, and no object of meditation.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye continued: “This is the true nature of the mind, settled into itself, but we are unable to believe it.” Resting in the true nature of our mind is the experience of our mind’s ultimate nature. But we don’t believe this and think that our mind’s ultimate nature can only be found outside the ordinary experiences that we have of our mind. We anticipate a stunning revelation of some kind in the future. We hope that we will then be able to point to it and think that we will call it “the real experience.” Whereas, in fact, awareness that is untainted and clear is what is meant by the Tibetan term, “rang-rig rang-gsäl” (‘self-awareness self-clarity’). This is our mind’s true nature, and there is no other nature that is missing and needs to be sought or found. With this in mind, we recite the last line in the above verse: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that self-awareness be liberated into its ground.”

6) Mindfulness and Awareness

In the prevopis verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye taught the methods of resting our mind in its uncontrived, true state. In the following verse, he offered an explanation of the cause for our confusion. He wrote:

“Death is certain to come, but we are unable to take this to heart.

Genuine Dharma is certain to benefit, but we are unable to practice correctly.

The truth of karma, cause and effect, is certain, but we do not decide correctly what to give up and accept.

It is certainly necessary to be mindful and alert, but these qualities are not stable within, and we are carried away by distraction.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we stay mindful with no distractions.”

Four obscurations cause our bewilderment. They are: the obscuration of cognition, the obscuration of mental afflictions, the obscuration of meditative absorption, and the obscuration of habitual patterns. They can be summarized in two: the obscuration of cognition and the obscuration of afflictive emotions. They are like veils that prevent us from directly seeing our mind’s true nature and thus from attaining omniscience. There are two aspects of omniscience: wisdom that directly sees how things are and wisdom that directly sees how things arise and appear. To attain omniscience, we need to overcome and thus to relinquish our obscurations.

Obscurations can’t be discarded, because they are habits that are instilled in our mind stream through our mental, verbal, and physical actions. It’s necessary to engage in virtuous, remedial habits and in that way to replace the non-virtuous, disruptive ones that we created and have become accustomed to over a period of many lifetimes. If we practice mindfulness and awareness well and become more and more proficient, we will eventually become free from habitual patterns altogether, i.e., we will gain perfect un-distracted awareness. This is why it’s said in “The Short Dorje Chang Lineage Prayer”: “Un-distracted awareness is the body of meditation.”

To attain omniscience, it can be said that there’s no better practice than cultivating un-distracted awareness. Since we are constantly distracted by fixating on experiences and appearances, we aren’t free. Mindfulness and awareness are the antidotes that we practice to overcome fixation on things that please or displease us. A beginner is mindful and aware deliberately. These qualities of being are natural traits and spontaneous reactions for very advanced practitioners.

Looking at the discipline that is practiced by Shravakas, the two kinds of selflessness that are studied and realized by Mahayana followers, and the creation and completion stage practices connected to the Three Roots that Vajrayana disciples cultivate, we find that they are all based on mindfulness and awareness. Some people think that meditation means being in a deep trance. But that’s not meditation. The purpose of meditation is to realize our mind’s natural quality of clear and lucid self-awareness. It’s a quality that distinguishes us from any other kind of phenomenon and is therefore referred to as “an uncommon quality.” By cultivating and intensifying mindfulness and awareness, we live our lives more skilfully and thus lead a more meaningful life.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö taught about the shortcomings of failing to cultivate mindfulness and awareness in the above verse and wrote in the first line: “Death is certain to come, but we are unable to take this to heart.” Of course, we know that we will die, and we know that we don’t know when. But we don’t keep this in mind and as a result we lead our lives as though we will live forever.

Continuing: “Genuine Dharma is certain to benefit, but we are unable to practice correctly.” This means that we know that Dharma practice is of great benefit and that we should practice, but we give in to distractions or laziness and therefore don’t. Then, due to lacking mindfulness and awareness, as stated in the next line: “ The truth of karma, cause and effect, is certain, but we do not decide correctly what to give up and accept.”

Generally, few people intend to hurt others, and nobody wants to hurt themselves, but because of falling under the power of their afflictive emotions, they accumulate negative karma that is the cause of suffering. This is why many disciples take ordination and vows; they are skilful means of creating a strong framework for the practice of mindfulness and awareness and thus for ending mental afflictions that bring on the accumulation of negative karma.

In the fourth instruction of this verse, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye taught: “ It is certainly necessary to be mindful and alert, but these qualities are not stable within, and we are carried away by distraction.” This means that since we haven’t fully and perfectly realized mindfulness, we turn our attention outwards and are mindlessly fixated on external things. This deprives us of being in the state of luminous cognition or self-awareness. Therefore in the supplication of this verse we request our Lama to bless us so that “we stay mindful with no distractions.”

7) Determination

This verse teaches us about the importance of being determined and diligent. It is:

“ Out of previous negative karma, we are born at the end of this degenerate time.

All our previous actions have become the cause of suffering.

Bad friends cast over us the shadow of their negative actions.

Our practice of virtue is corrupted by meaningless gossip.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that we take the Dharma deep to heart.”

Unless we are an individual who doesn’t need to practice the stages of the path but can spontaneously realize the innermost meaning of the Dharma, it’s necessary to practice the gradual stages of the path. In doing so, we need to have fortitude, which is compared to having a bone in the heart. We are born in a time of great suffering, and it is the result of our intense mental afflictions and previous karma. “Bad friends” in this verse is a metaphor for the enemy of ego-fixation within that obscures us from practicing the Dharma. Looking at the lives of great Lamas, we see that they were very determined and diligent. We are carried away by meaningless activities and therefore request our Lama to bless us so “that we take the Dharma deep to heart.”

8) Perseverance

The words in the first line of the previous verse, “the end of this degenerate time,” describe our state of being. This is discussed more fully in the following verse, which is:

“At first, there is nothing but Dharma on our mind,

But at the end, the result is the cause of samsara and lower realms.

The harvest of liberation is destroyed by the frost of non-virtuous activity.

We, like wild savages, have lost our ultimate vision.

Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion.

Bless us that within we bring the genuine Dharma to perfection.”

At the start, a student might have strong faith in the Dharma and wish to practice a lot to attain liberation from samsara, but their faith and practice diminish after a short while. Finally, they return to being solely involved with samsaric ways. This happens to people whose attitude wasn’t pure to begin with or who became corrupted because they weren’t determined and diligent and therefore lacked fortitude. Sometimes people turn away from the Dharma because of obstacles. For example, after having completed a three-year retreat, some people throw anything that reminds them of Dharma away, or some people seek an environment in which not even the sound of Dharma can be heard, or some people turn Dharma into a business. All these things are done during times that are called “the age of decadence.” This means turning the intention to attain liberation from samsara into samsara. It’s described by metaphor in the third line of the above verse: “The harvest of liberation is destroyed by the frost of non-virtuous activity.” Therefore: “We, like wild savages, have lost our ultimate vision.”

In the last line of this verse, we request our Lama to bless us so that we keep the sacred Dharma as Dharma and, instead of running around in circles and turning the Dharma into a source for more suffering, that we complete the practice to perfect awakening, i.e., Buddhahood. The prayer that Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye composed and that we recite is: “Lama, think of us, behold us swiftly with compassion. Bless us that within we bring the genuine Dharma to perfection.”

The Gradual Path of Practice in Lines of Request

In this section of “The Supplication,” Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye offered a summary of the spiritual path to awakening in the form of a request to our Lama. The first line is:

“Bless us that repentance arises deep from within.”

The above line connotes that we aspire to fully realize that samsara is meaningless and request our Lama to bless us so that we give rise to perfect renunciation. Then:

“Bless us that we curtail all our scheming.”

As stated in the next line, we also aspire to never again make plans based on misconceptions and therefore we pray:

“Bless us that from the depth of our heart, we remember death.”

Continuing:

“Bless us that we develop certainty in the laws of karma.

Bless us that our path is free of obstacles.

Bless us that we are able to exert ourselves in practice.

Bless us that we bring difficult situations onto the path.”

Sometimes we are confronted with situations that are impediments and it’s necessary to bring them to practice. Therefore Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye composed the next line that is:

“Bless us that antidotes, through their own power, are completely effective.”

There is an antidote for every mental affliction that we have and that we need to recognize the moment it arises so that we can overcome it. Sometimes an affliction is stronger and conquers the remedy we tried to apply. Therefore we request our Lama to bless us so that the antidotes we apply are effective.

The summary is continued with the request that our Lama bless us so that - at all times and in every situation - we rest in the true nature of our mind:

“Bless us that genuine devotion arises.

Bless us that we see the very face of the mind’s true nature.”

Continuing:

“Bless us that self-awareness awakens in the center of our heart.

Bless us that delusive appearances are completely eliminated.

Bless us that we achieve enlightenment in one lifetime.”

The first two lines of the last verse of “The Supplication” are:

“We pray to you, precious lama.

Kind lama, lord of dharma, we call out to you with longing.”

Having sincerest, one-pointed devotion for our Lama and being fully committed to him, we pray and make the request:

“For us, unworthy ones, you are the only hope.

Bless us that your mind blends with ours.”

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye closed “The Supplication: Calling the Lama from Afar” with those words.

It’s very beneficial to recite or chant “The Supplication” every day or whenever possible and to examine our mind according to the instructions that are offered in this sacred song of profound meaning. This Doha consists of more than just words. It is a sublime blessing and is an exalted inspiration to practice the Dharma. – Thank you !

A Selection of Questions & Answers

Student: “Do we chant ‘Calling the Lama from Afar’ in the Bardo?”

His Eminence: It would be very good if you could. The main thing is to chant it now so that it becomes a habit. There will certainly be nothing wrong with chanting it in the Bardo, if you can do that. The main thing is to prepare for the Bardo by chanting it now.

Next question: “Can you please explain Rime?”

His Eminence: The late Kalu Rinpoche taught that it’s much more practical and effective to stick to one Lineage. A number of people claim to be Rime practitioners and they try to collect and practice all teachings from the different schools of Buddhism. This indicates that they do not trust one Lineage. It would be very hard to keep all the commitments that would be required if one were a follower of all Lineages. I think that Rime means respecting all Lineages, all teachers, and all teachings of the Buddha. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye, Jamyang Khyentse, and Chogyal Lingpa were extraordinary Rime masters, nevertheless, Chogyal Lingpa was Nyingmapa and Jamyang Khyentse was Sakyapa. Jamgon Kongtrul did much work for all Lineages, including for the Bon Tradition, by writing “The Five Treasures,” but his monastery was Palpung of the Kagyu Tradition. Practicing one Lineage doesn’t imply that you are sectarian. A sectarian is someone who boasts, “My Lineage is better than others.” If you think like this or criticize others, then you are sectarian. Practice your own Lineage and respect others. That is Rime. All Lineages have remained unbroken until now, otherwise Rime couldn’t continue.

Question: “Would you please explain freedom from attachment?”

His Eminence: There are two kinds. One is what could be called “virtuous passionless-ness,” which is renunciation. The other could be called “stupid passionless-ness,” which is the inability to get anything done or laziness. Obviously, the first is a good quality and the second isn’t.

Question: “If one has renunciation and seeks liberation, would one have to abandon all one’s aims, from a worldly perspective?”

His Eminence: It’s not the case that somebody who has turned his mind towards the attainment of liberation and omniscience and who has thus given rise to correct renunciation is aimless. Renunciation doesn’t mean being aimless or trying to escape. Trying to escape from reality is a way of thinking, e.g., thinking, “Oh well. The world doesn’t matter. Dharma doesn’t matter. Nothing matters, so I won’t take on any responsibilities.” Correct renunciation means acting in a way that is beneficial for the country one lives in and being in harmony with the respective culture. On a worldly level, it’s necessary to differentiate between what is virtuous and what is non-virtuous.

Question: “Would you please explain what it means for the mind to arise as the three Kayas?”

His Eminence: Mind’s essence is emptiness, the Dharmakaya. Its natural clarity or lucidity is the Sambhobakaya. The mind’s thoughts are the Nirmanakaya. Some people think that the three Kayas are physical bodies, but that’s not what is meant.

Next question: “Why don’t we recognize the Bardo?”

His Eminence: If we are able to recognize the Yidam deities after we have died, then we will become liberated in the Bardo. But it’s necessary to have experienced them through practice during life. Death sets in when our elements have dissolved. During that time, beings are extremely terrified. However, a practitioner who is accustomed to meditation can recognize the appearances that arise to his mind then and can attain liberation as a result.

Next question: “What is ignorant pride and how do we deal with it?”

His Eminence: Ignorant pride is having a misconception, like thinking you have qualities that you don’t have. There are two remedies that you can apply, firstly, meditating on what is displeasing. Practically speaking, the main thing is to uphold mindfulness and attentiveness; this is the second remedy.

Next question: “When you spoke about karma, you mentioned that our negative karma drives us to take birth in lower realms. Does this mean that our karma ripens in the Bardo?”

His Eminence: There are different kinds of karma. For example, one kind is called “the ripening of karma that can be seen directly.” There is also what is called “the karma of the uncertain time of ripening.” So, there are cases in which the result of an action is experienced right away. Everybody wants to be happy and free of suffering, but nobody has same experiences. This is due to individual karma. The verse about karma in “The Supplication” is about the infallibility of karma.

Next question: “Are there specific teachings that help us eliminate our negative karma?”

His Eminence: It’s recommended to meditate the four preliminary contemplations that help turn the mind towards the Dharma, particularly to contemplate and meditate on karma. There are many Sutras and treatises that offer extensive explanations of karma. If you study those texts, you should be able to gain certainty of karma.

Same student: “What are the four thoughts?”

His Eminence: The four thoughts are a foundation for practice. They are contemplating on the precious human birth, on impermanence and death, on karma, and on samsara.

Next question: “In which way does the Nirmanakaya benefit beings?”

His Eminence: It benefits them according to the situation and their ability to receive help. Lord Buddha was a Nirmanakaya and performed twelve beneficial deeds in all. He displayed birth, became enlightened, taught the Dharma, passed into Nirvana, and so forth. To contact and benefit beings, the embodiment of a Nirmanakaya will employ the skilful means of walking, eating, sleeping, sitting, talking, and so on. The Buddha said: “In the past, I never turned the Wheel of Dharma. I am not turning it now, and I won’t turn it in the future. In accordance with their needs and capabilities, I have bestowed upon beings a great amount of ways to approach and practice the Dharma.”

Concluding Words & Dedication

This has been a short seminary and retreat, but it has been effective because you came here and endured the hot weather. I sincerely hope that these instructions help you understand and practice the Dharma with all your heart. I also hope that you don’t feel that this is the last retreat, and I hope that you will have more retreats of this kind in the future.

I want to respond to a complaint many of you have made, that many Rinpoches come here and give different initiations. You have enough initiations now, and I think it is very important for you to put them into practice. The best way would be for the Dharma centers to organize retreats, but not when it’s very hot outside, rather, when it’s cool and refreshing during the winter months. As said, I hope you don’t feel that this has been the last retreat.

I want to say that I am very happy that we had the opportunity to do this retreat together, especially that you ertr very patient and are eager to practice the Dharma. I feel that you really have confidence in the teachings. What else should I say? Let us dedicate the merit together.

Through this goodness, may omniscience be attained

and thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

that is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

May Bodhichitta, great and precious,

arise where it has not arisen.

Never weakening where it has arisen,

may it grow ever more and more.

From now until enlightenment, supreme Lama,

may we always serve and rely on you.

May we persevere in practice and complete the path,

giving up what is negative and perfecting the positive.

His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche presented these instructions in Taiwan, 1991; they were transcribed by Gaby Hollmann in that same year from the tapes that Lee Chin Yun from Nantou, Taiwan, had kindly sent and were typed and revised in 2013 from the article that appeared in the 28 th issue of “Thar Lam,” April 2013, pages 38-59. The translation of the Root Text was made by Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche and Michele Martin. It is indebted to a version by the Nalanda Translation Committee in “Journey without Goal” by Chogyam Trungpa (Shambhala, 1985) and is printed in: “His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche. In Memory,” Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang, Rumtek, Sikkim, 1992, pages 42-73. – The photo of His Eminence was taken during this occasion in Taiwan. – The photo of the beautiful flower was taken and offered by Lena Fong. This article is copyright and may not be translated or published anywhere, Munich, 2013.

|