| [98]

Gaining Certainty of the View – Part 4/6

Instructions on Chapter 7.3 of

“The Compendium of Knowledge – Shes-bya Kun-khyab mDzöd”

composed by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great

presented by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

at the Thrangu House, Oxford, England, in 1995

5.2.2. No Self of a Person

5.2.2.1. The Meaning

- The Obvious and Subtle No Self of a Person

5.2.2.2. The Nature of the Belief in the Self of a Person

5.2.2.3. Why Belief in the Self of a Person needs to be Eliminated

5.2.2.4. No Self of a Person in the Different Traditions

5.2.2.5. The Madhyamaka Analyses of the No Self of a Person

5.2.2.5.1. The Five Skandhas

5.2.2.5.2. The Twenty Views of that which is Destroyed

5.2.2.5.3. Ten Mistaken Views of the Self & the Remedies

5.2.2. No Self of a Person

5.2.2.1. The Meaning

The Root Text:

“What distinguishes the views of non-Buddhists from (those of) Buddhists is (the assertion of) a self in the individual.”

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye explained the reason no self of a person is taught and that it is important to differentiate between Buddhism and the beliefs of followers of other religious traditions. It can be argued that individuals who seek and take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha are Buddhists and that those who have or do not are not Buddhists. But this is a distinction that is based on external factors. The real distinction between following the Buddhist path or the non-Buddhist path has to do with appreciating and acknowledging the no self of a person. Individuals who believe that a self of a person is a truly existent independent material or immaterial entity belong to non-Buddhist traditions. Individuals who do not believe in and negate the true existence of a person belong to the Buddhist tradition.

- The Obvious and Subtle No Self of a Person

What is the belief in a self of a person? There are two kinds, the obvious and the subtle. As mentioned earlier, belief in a self is an instinct that is spontaneously present in young and old alike. Nobody was told and did not need to learn to think, “I” or “I am.” To have belief in a self, nobody needed to investigate theories and find answers to questions such as “Is the self permanent or impermanent? Is it large or small, material or immaterial?” and so on. Without the need to ask and contemplate such questions, the thought or feeling of having a self is and has been present in everyone throughout past lifetimes. Everyone has the subtle tendency of believing in a personal self.

There is the obvious belief in a self. It is the conceptually fabricated imputation of that belief. Since belief in a self of a person is generally accepted by everyone, some scholars examine to see what it is like. They search for it by asking, “Where is the self located? What does it consist of? What is its nature?” The Buddha taught that the self is devoid of an own nature, that there is no self, and that believing in a self is a delusion. Scholars of every other tradition believe that there is a self and examine to see whether it is permanent, impermanent, material, or immaterial. By thinking that it truly exits and in their attempt to find it, they might come to the conclusion that the consciousness is the self. Others can disagree and say, “No, the consciousness is unstable because it continually changes. So the self must be a material form.” Others might reject this idea and argue, “No, the self is impermanent because it changes from one life to the next.” While attempting to find the self that they believe in and by analyzing and disputing in such ways, they come to different conclusions. Sometimes they identify the self with the five skandhas, sometimes with the body, and sometimes with the mind. They do not look directly at what they think is a self but put all their attention on questions about it. Even if people try to develop an understanding of no self through meditation and have experiences, they still tend to belief in it. They might think that the clarity, cognition, and awareness they experienced through meditation practice are the self. It is possible to gain a theoretical understanding of no self through analytical reasoning and through meditation, but it is important to know that all mentally constructed imputations are delusive. The Buddha looked to see what the nature of the self of a person is. He looked at the mind directly and attained realization that a self of a person does not truly exist.

It is necessary to overcome and eliminate belief in a self. How do we do this? Just thinking, “Well, I will get rid of this belief” will not do. The cause of this innate belief needs to be eliminated. Since we have been habituated to this belief for countless lifetimes, merely understanding that it is a delusion by examining for ourselves and seeing that there is no self in the skandhas, in the body, and so on will not bring about cessation of the belief in a personal self. Our deeply ingrained belief in a self can only be removed by becoming habituated to meditating on the subtle no self.

In the Kadampa tradition, there are the teachings on mind training. Dipamkara Atisha taught disciples to reflect all the suffering and difficulties that are experienced in samsara on account of cherishing the self more than others. Furthermore, it is possible to diminish attachment to the self by thinking about the great benefit that comes from cherishing others more highly than oneself. In the Vajrayana tradition, there is the forceful practice of Chöd, ‘cutting through,’ i.e., cutting through belief in a self.

5.2.2.2. The Nature of the Belief in the Self of a Person

“Its essential nature is innate grasping onto ‘I’ and ‘mine.’”

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye wrote that there are two kinds of innate beliefs in a self. One is the belief in an “I” or “me” and the other is the belief in the thought “mine.” Since the object of our belief in a self is not definite, at times we think of our mind as “me” and our body as “mine.” At other times we think of our body as “me” and our mind as “mine,” or we think our body and mind together are “me” and our possessions are “mine.” Our belief in what we consider “mine” can relate to very big things, e.g., “my land, my country, my world,” or to tiniest things. Why is there no definite object for our belief in a self? Because our belief is a delusion.

5.2.2.3. Why Belief in the Self of a Person needs to be Eliminated

“(The self of the individual) should be negated because on the basis (of it), ‘other’ is perceived (and thereby) all (afflicted) views arise.”

In the third part of the section “No Self of a Person,” Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye wrote about the reason it is necessary to negate the belief in the self of a person. The reasoning he offered is attributed to a statement that Chandrakirti made, which is, “When one believes that there is a self, where in fact there is no self, then automatically one creates that which is other than the self and thus there is duality of self and other. As a result, one feels that the self is special and cherishes it above everyone else. Having self-cherishing, there is attachment to the self and aversion and rejection of anything good about others. Then pride, envy, anger, and so on arise in one’s mind. That is how one creates one’s own difficulties and sufferings. Therefore, one needs to negate and eliminate the belief in the self of a person.” Chandrakirti continued, “When one believes in and is attached to an ‘I’ or ‘me,’ then one is attached to anything one considers ‘mine.’ This will engender difficulties.”

For example, we might think, “My things have not gone well and have not been good for me.” We suffer when we think like this, and the source of all problems and sufferings is attachment to the thoughts “I” and “mine.” That is why it is necessary to negate and eliminate those beliefs.

It is easy to negate belief in what we consider “mine.” For example, if we see somebody drop a watch in a shop and it broke, we would simply think, “Oh, somebody dropped a watch and it broke.” But if we notice a small scratch on our watch, we would probably have an unpleasant feeling and think, “Oh no, mine has a scratch.” We had no sensation when we saw the watch break while in the shop but we are upset when we notice that our watch has a little scratch. What is the difference between the two watches? Believing that the scratched watch is “mine.” Believing in “mine” causes unpleasant sensations. What justifies the thought, “my watch”? There is no “my” in the watch that is made of the same material as the one that broke. A “my” cannot be found in the watch we call “mine,” so believing “It is mine” is not a part of the watch. In fact, the idea “mine” has no reality and is the source of unpleasant sensations that arise, in the case of the watch, from a scratch. In the same way, we are usually upset when we learn that larger things we call “mine” go wrong, e.g., when we hear about trouble in our neighbourhood or country. If we become free of believing in the true existence of things that we consider “mine,” problems and difficulties will not upset us.

5.2.2.4. No Self of a Person in the Different Traditions

“Although (they have) different ways of realising (emptiness), all four philosophical systems realise (the mere lack of a self in the individual).”

As explained earlier, the four traditions of Buddhism are divided into three groups. The Vaibhashikas and Sautrantikas teach the obvious no self of phenomena and give general teachings on the no self of a person. Since these two systems are similar, they are counted as one. The Cittamatrins are counted as one, and the Madhyamikas are seen as the third group. The Cittamatrins and Madhyamikas offer definitive teachings on the subject of no self of a person.

5.2.2.5. The Madhyamaka Analyses of the No Self of a Person

This section on the Madhyamaka analyses of the no self of a person does not deal with experience, rather, is an analytical approach.

The Buddhist analytical approach to establish the no self of a person uses the example of a chariot. The answers are given to questions that are asked. The questions are: “Is there such a thing as a chariot?” Relatively speaking, yes, it appears that there is a chariot. It can be loaded with things that are brought from one place to another, therefore, it seems as if it exists. Madhyamaka proponents carry out the logical reasoning in this way: Although it seems to exist in relative terms, in actual fact there is no such thing as a chariot. Are the wheels the chariot? No, they are not the chariot but are wheels that roll and that cannot fulfil the function of a chariot. Is the axle the chariot? No, and it cannot fulfil the function of a chariot. Is the platform that holds a load the chariot? No, the platform cannot take things from one place to another. Now, a chariot is composed of wheels, an axle, a platform, and so on, but none of the parts is the chariot. Well, is the chariot separate from its parts? No, it is not. One cannot say, “This part is the chariot” and ignore the other parts. Is the chariot identical with the wheels and other parts? No, because each part has a different function. Looking at the wheels, one cannot say that the wheels are based on the chariot or that the chariot is based on the wheels. One cannot say that the form and shape of the entire object is the chariot because many parts are assembled so that the chariot has a form and fulfils the function of a chariot. One sees the assembled parts that are able to fulfil that function and calls that object “a chariot.” The name is given to that object, but the true existence of a chariot can not be found. In Madhyamaka, this method of reasoning is also carried out for what is called “a self.”

5.2.2.5.1. The Five Skandhas

“The five skandhas are not the self; the self does not possess them. (And the two) do not (act as a support) for each other.”

Five skandhas constitute a living being. The five skandhas (‘aggregates’) are: physical forms, sensations, identification, mental activities, and consciousness. Looking at each skandha, Madhyamikas ask, “Is it the self`?” No, it is not. Does the self own the skandhas? No. Is the self identical with the skandhas? No. Is the self the shape of the skandhas? No. It is possible to call the collection of skandhas which carry out a function “self,” but, in fact, there is no self that is identical with nor that can be separate from the skandhas.

5.2.2.5.2. The Twenty Views of that which is Destroyed

“(The self of the individual is refuted by reasoning such as ‘the chariot,’ which proves these twenty points.”

By going through each of the following twenty points, we will discover that the self does not exist. Using the logical analyses that we applied when investigating the self of a chariot, we can analyse and see that there is no self in relation to the skandhas.

(1) – (5) We might think that the skandha of our physical form is the self, but it is not. Or we might think that the second skandha, the aggregate of sensations, is the self, or that the third skandha of identification is the self, or that the fourth skandha of mental activities is the self, or that the fifth skandha of consciousness is the self. But none of the skandhas are the self. Believing so means having five incorrect views.

(6) – (10) We might think that one of the five skandhas accompanies the self, i.e., that the self and the form coexist, or that the self and the sensations coexist, or that the self and identification coexist, or that the self and mental activities coexist, or that the self and the consciousness coexist. Since none of these five views is right, they are wrong.

(11) – (15) It is also possible to think that form is based on the self, or that sensations are based on the self, or that identification is based on the self, or that mental activities are based on the self, or that the consciousness is based on the self. These five views are also wrong.

(16) – (20) It is also possible to think that the self is based on each skandha, i.e., on form, sensations, identification, mental activities, or consciousness. These five views are also not right.

To realize no self, we can search for it by going through our body, from the top of our head to the soles of our feet. Some people do this meditation and by not finding the self, they understand and realize that there is no self.

5.2.2.5.3. Ten Mistaken Views of the Self and the Remedies

“In ‘The Madhyavantavibhanga,’ ten ways of conceiving of a self in the individual are remedied by ten ways of being expert. There are also many other such reasonings.”

The ten mistaken views of the self are: (1) Viewing the self as unitary; (2) viewing the self as a cause that gives rise to other things; (3) viewing the self as the consumer that enjoys objects; (4) viewing the self as the creator; (5) viewing the self as having power over objects; (6) viewing the self as permanent; (7) viewing the self as defiled; (8) viewing the self as being the basis for purification; (9) viewing the self as having yoga; and (10) viewing the self as liberated and not liberated.

The ten remedies to eliminate these ten mistaken views of the self are: (1) Being learned in the skandhas; (2) being learned in the 18 dhatus (‘elements or components of perception’); (3) being learned in the 12 ayatanas (‘6 internal and 6 external sense bases or gates of perception’); (4) being learned in dependent origination; (5) being learned in the appropriate and inappropriate; (8) being learned in the powers; (7) being learned in time; (8) being learned in the Four Truths; (9) being learned in the Yanas (‘vehicles’); and (10) being learned in the composite and non-composite.

Continued.

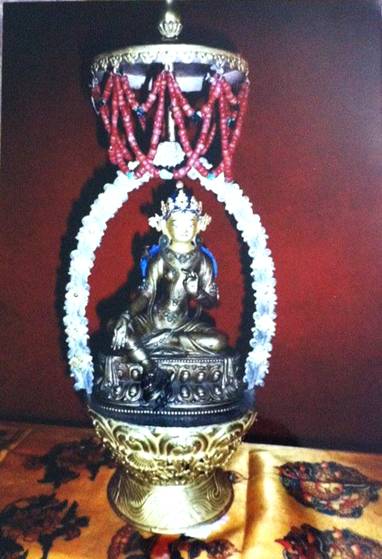

In the caption of the photo of Green Tara that Belinda Woo posted on her FB (on Aug. 30, 2011), she wrote: “This Tara statue spoke to Jamgon Kongtrul the Great after his prostration to her. Ornaments were added to the statue by HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. Statue is kept at Palpung Drubkang in Tibet.”

The translation of the teachings that Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche presented in Tibetan were simultaneously translated into English by Peter Roberts. The Root Text, “Gaining Certainty about the View,” was translated under the guidance of Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche by members of the Marpa Translation Committee and was published in Kathmandu, Nepal, by Modern Printing Press Ltd., in 1994. The teachings of this seminary were transcribed & edited from the recordings by Gaby Hollmann in 1996 and in 2013 the manuscript was revised & edited again for the Dharma Download Project of Karma Lekshey Ling Shedra, Nepal. This rendering is for personal studies only; it may not be published anywhere else, and it may not be translated into another language without prior permission from everyone mentioned here. Copyright, Munich, 2013. – May virtue increase!

|